Apicius' De Re Coquinaria

Welcome to FabulousFusionFood's Information page on Apicius' De Re Coquinaria (On Cooking) — This page gives you information about the most famous Roman Cookbook: the De Re Coquinaria (The Roman Cookery of Apicius) traditionally attributed to the gourmand 'Apicius'. Here you will find information about the book, its history and the types of recipes contained within. I also provide some information about Apicius, and Vinidaris who later added to the book.

As well as information on Apicius and his recipes, I also include links to each chapter of the book (these have the original Latin text and an English translation) as well as providing links to modern versions of the recipes that you can cook at home. Below is also a glossary of various terms and ingredients that might be unfamiliar, as well as a list of substitutes. This site aims to provide the most complete collection of Roman recipes available on the web today.

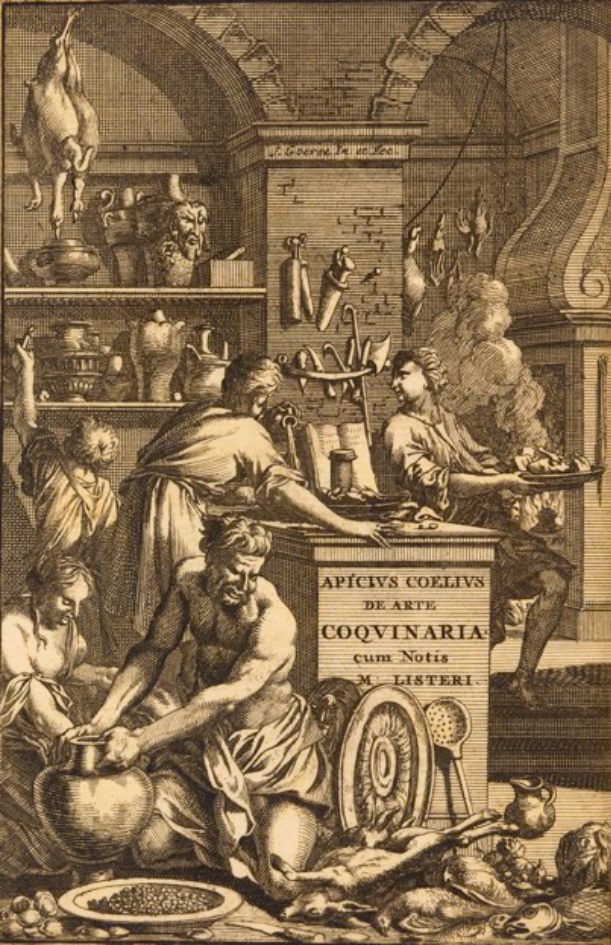

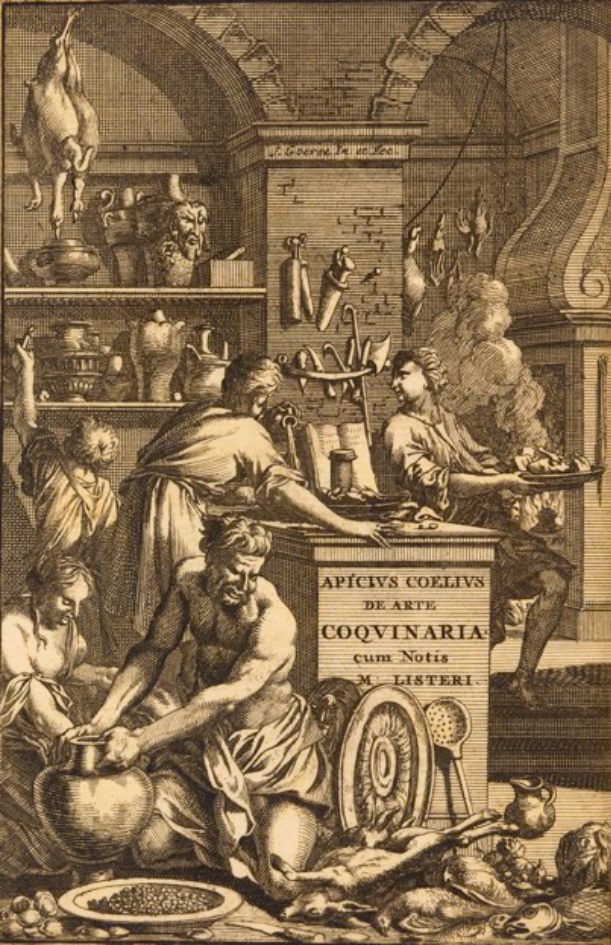

Frontispiece of the second edition of Martin Lister's

Frontispiece of the second edition of Martin Lister's

privately printed version of Apicius 1709.

Apicius is a culinary text that's intended to be used in the kitchen. In the earliest printed editions, sometimes known under the title Ars magiricus, it was most usually given the overall title De re coquinaria ('On the Matter of Cooking'; or simply 'On Cooking'), and was attributed to an otherwise unknown 'Cœlius Apicius' (or 'Apicius Cœlius'), an invention based on the fact that one of the two extant manuscripts is headed with the words 'API CAE'.

The text itself is organised in ten books (or chapters) that, in essence, are arranged in a manner very similar to any modern cookbook. Namely:

The text however, is broken, indicative of many redactions. With some recipes in chapters not consistent with the chapter title. Some recipes are present in duplicate, some are believed to be truncated, sometimes a line seems to be missing.

In a completely different manuscript, there is also a very abbreviated epitome entitled Apici Excerpta a Vinidario, a 'pocket Apicius by Vinidarius, an illustrious man', that seems to have been penned as late as the Carolingian era. This text survives in a single 8th century uncial manuscript. However, despite the title, this booklet is not an excerpt from the earlier Apicius manuscript we have today (as a result it is reproduced in full on this site. It contains text that is not in the longer Apicius manuscripts; which suggests that either some text was lost between the time the excerpt was made and the time the manuscripts were written, or there never was a 'standard Apicius' text, because the contents changed over time as it was redacted and adapted by various readers of the text.

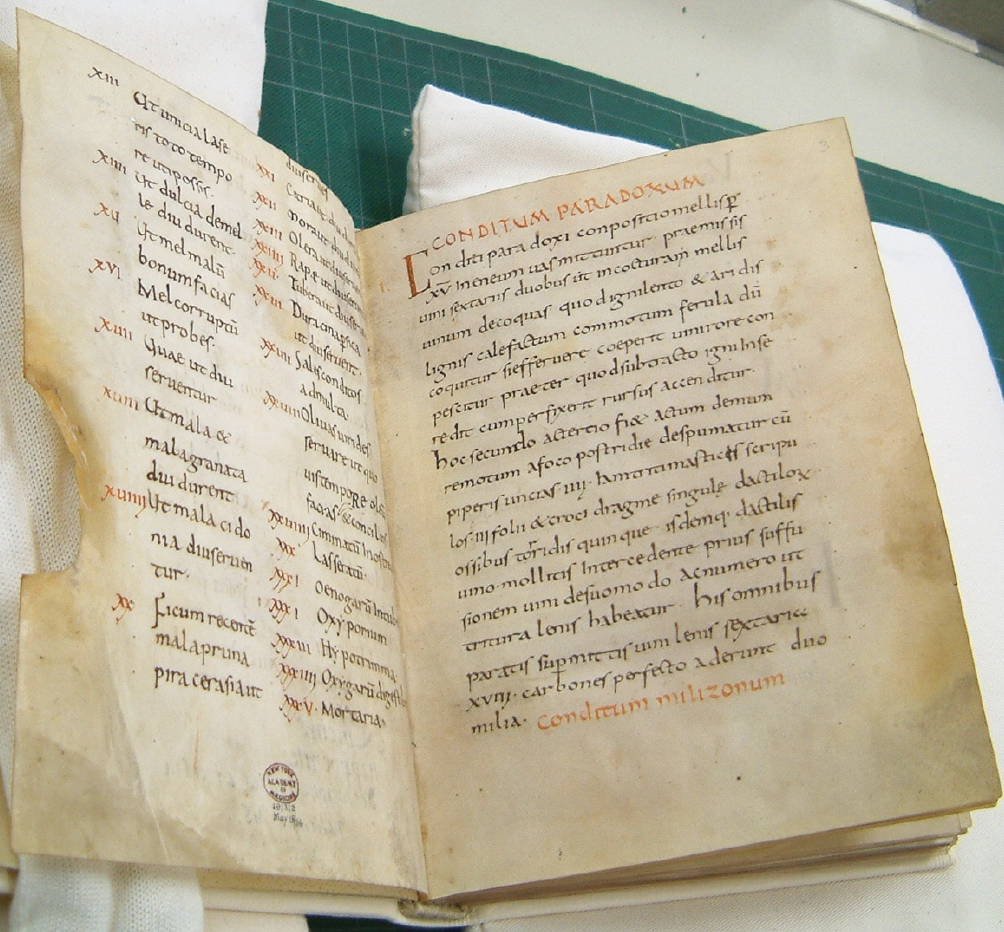

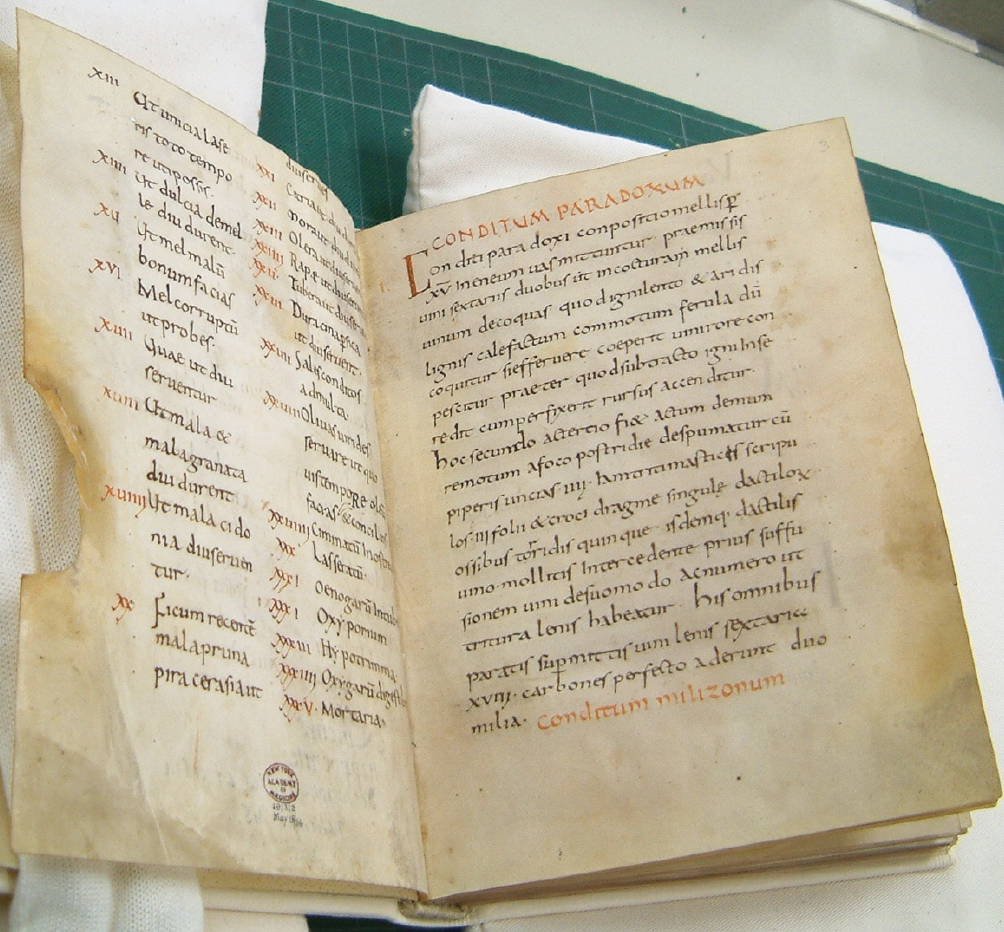

As a note, though Apicius is thought to have been compiled during the 4th and 5th centuries and it is possible that some recipes may date back to the time of the historical Apicius during the 1st century CE, the oldest extant manuscript we have is penned in the 10th century (c. 900 CA) in monastic-style uncial. This came from the monastery of Fulda in Germany, which was acquired in 1929 by the New York Academy of Medicine. An example page is given here, so you can see the text.

Imagined portrait of Marcus Gavius Apicius from

Imagined portrait of Marcus Gavius Apicius from

Alexis Sawyer's Pantropheon, 1853.

The first of these was Marcus A. Apicius who lived about 100BCE during the time of Sulla. He was famed for the reputation of his good table even during later times. However, the Apicius that most authors focus on is Marcus Gabius Apicius (sometimes Gavisu) who lived during the times of Augustus and Tiberius (80BCE to 40CE). He is described by Athenaeus (in his Deipnosophistae), one of the chief writers of the time who references food and food culture is this:

Athenaeus also informs us that Apician recipes were famous and that many recipes were attributed to him. However, Apicius is not the only gourmand who has recipes attributed to them in the De Re Coquinaria. The most notable of these is Vitellius (who ruled Rome between January and June 69CE), a famous glutton. He ante-dates Apicius and it would seem that, rather than having been written by Apicius, the book was more likely dedicated to him. Indeed, 'Apicius' may even have become a short-hand for anyone who enjoyed their foods. So that a dedication to 'Apicius' in the general would be one to all gourmands.

Even then, the prototype for the generalized 'Apicius' is probably Marcus Gabius Apicius as he is the most famed of all bon-vivants. He established a school for the culinary arts, and according to such notable writers as Seneca and Martial, it is said that Apicius spent his vast fortune on food and when his reserves of gold had dwindled he took his own life, fearing that he might have to starve to death one day.

As the poet Martial writes in his Epigrams 3.22:

In truth, even by the end of the first century CE, the very name of 'Apicius' had become a cliché for wealth and culinary excess. As Juvenal writes in his Satires (II. 2–3)

What greater joke tickles the ear of the people than the sight of a poor Apicius?

Whether Apicius was the author of the volume, or simply a figure or an archetype it was dedicated to, the De Re Coquinaria remains the first European cookery book, and an invaluable window on Roman food and Roman cookery. Many of the recipes are quite familiar in some ways, others are surprising in terms of their combination of flavours and even more are extremely modern in their use of fish sauce to provide the umami flavour to food (which we use anchovy essence, mushrooms and Worcestershire sauce for).

Image of De Re Coquinaria Fulda MSS c 900 CE.

The De Re Coquinaria is preserved as two Medieval manuscripts dating from the ninth century. The first of these was written in Tours, France, in the Tours scriptorum under the tenure of Abbot Vivian (844–851 CE). The second was probably produced in Fulda, Germany c 900 CE.

Image of De Re Coquinaria Fulda MSS c 900 CE.

The De Re Coquinaria is preserved as two Medieval manuscripts dating from the ninth century. The first of these was written in Tours, France, in the Tours scriptorum under the tenure of Abbot Vivian (844–851 CE). The second was probably produced in Fulda, Germany c 900 CE.

The Tours manuscript, (now in the Vatican Library [Urb. lat. 1146) is a highly decorated manuscript and was almost certainly not intended for everyday use in the kitchen. The Fulda manuscript seems to have come to Italy in 1455 and was acquired by the Philips collection, Cheltenham in the early nineteenth century. It now resides in the library of the Academy of Medicine, New York.

Both manuscripts derive from a common antecedent which seems to have been located at Fulda. This was extant in the fifteenth century, when Poggio made his excerpts.

In the fifth or sixth century, an Ostrogoth, Vinidarius, who lived in Northern Italy made some excerpts of Apicius and these now survive in a single eighth century unical manuscript, the codex of Salmasius, sæc. VIII, Paris, lat. 10318.

The language of both the extant early manuscripts is popular (Vulgate) Latin and not the classical Latin of Apicius' time (assuming he existed). Indeed, if there was an original classical Latin antecedent this was copied and re-worked by an editor who lived in the late fourth or early fifth centuries.

Indeed, this unknown editor may be the true creator of the Apicius manuscript, as there is evidence that the brought together recipes from several sources (one of which was the cookery of Apicius, the other being the writings of Apuleius).

As such, there may never have been a 'starndard Apicius', as each generation updated, extended and amended the text to suit their own culinary purposes. Indeed, Vinidarius' excerpts suggests at the existence of at least one other version of Apicius with recipes that do not exist in the extant manuscripts. As a result, Vinidarius' excerpts are, today, invariably included as an eleventh chapter to supplement the ten of the standard Apician cookbook that has come down to us.

This edition seems to have been re-printed in Venice c. 1500, but it was printed anonymously and without a date (probably to try and avoid any difficulties regarding the Milanese privilege), which was then used as the model for the edition of Ioannes Tacuinus (Venice, 1503).

In 1541, Albanus Torinus produced the first critical edition of the text (Basle, 1541) that gave a partial translation into humanist Latin. The following year, Gabriel Humelberg published a new edition (Zürich, 1542), basing his texts on good manuscripts, as well as well as what he calls an antiquum manuscritum exemplar now, unfortunately, lost to us.

This was the edition that Martin Lister (physician to Queen Anne) followed closely for his own edition (London, 1705; Amsterdam 1709). The first translation was into Italian in 1852, followed in the 20th century by two translations into German and French.

The first truly reliable edition of the Latin text was that of C Giarratano and F Vollmer (Leipzig, Teubner, 1922). Vehling made the first translation of the book into English under the title Cookery and Dining in Imperial Rome. It was published in 1936. The translation is still in print, having been reprinted in 1977 by Dover Publications. Today, however, this version is of little more than historical interest only and several more recent translations exist, including the one presented on this site.

The Flavours of Roman Cookery

Roman Herbs and Spices

A Guide to Roman Ingredients

The Roman Kitchen

Defritum: Referred to in some translations as 'boiled wine', defritum is wine boiled down to half its original volume before use.

Caroenum This is boiled Must (must is essentially very young wine [at the first stage of fermentation]). The closest modern equivalent would be a sweet young white wine or grape juice. Boil until the volume is reduced by half.

Sapa: This is must (grape juice) that is boiled down to a third of its original volume. It was made with sweet wine and the final product was both very thick and sweet. It was used as a sweetener and flavouring as well as a preservative (in place of honey).

Liquamen: Traditionally this is thought of as a 'cheap form' of fish sauce (see garum below). But, reading Apicius carefully reveals that liquamen is used as a generic term for a sauce or stock of any kind. In many cases this would have been a fish sauce, but could have been any kind of meat, fowl, vegetable, shellfish, fish or seafood sauce. Indeed, the inference seems to be that the cook should know what kind of stock or sauce was appropriate to the sish.

Garum: Fermented salted fish. This was a common addition to Roman food. The closest modern equivalent would be Nam Pla, Thai fish sauce. However, if you are interested in making your own Roman fish sauce, I do have a recipe: how to make Garum. Note that, in some circumstances, Liquamen (see above) can also refer to fish sauce.

Passum This is a sweet wine sauce made by adding honey to must (or raisin wine) and boiling until it has thickened.

Puledimu This is Pennyroyal (Mentha pulegium). Ordinary garden mint can be substituted.

Sautreia This is Summer savory Satureia hortensia. The commoner winter savory can be substituted for this.

Silphium See laser, above.

Spikenard This is the plant, Nardostachys grandiflora (Indian spikenard) or Nardostachys jatamansi (Himalayan spikenard), [also known as nard, nardin, and muskroot] an aromatic plant with small leaves and red-purple flowers that's a member of the Valerian family and a native to northern region of India and Nepal as well as the Himalayas of China. This is used frequently in aromatherapy oils. The oil was known in ancient times and was obtained as a luxury in ancient Egypt, the Near East, and Rome, where it was the main ingredient of the perfume nardinum. The dried root, used as a spice, be obtained from a specialized supplier. An alternate is to use equal portions of fennel and lavender a fifth of the final quantity of valerian root (note, valerian is a sedative and some people are very sensitive, use sparingly. Lavender should not be consumed by pregnant women). The powdered root was used commonly as a spice during Roman times and in Medieval Europe it was part of the spice blend used to flavour Hypocras. For more information about spikenard, and spikenard recipes see the Spice Guide entry for Spikenard.

Safflower This is the plant, Carthamus tinctorius, a highly branched, herbaceous, thistle-like annual that is growh both for its seeds (used to make oil) and for the dried petals that can be used as a saffron substitute. In ancient times, it was prized by the Egyptians and the use in Apicius clearly demonstrates the Egyptian antecedents of some of the recipes (where the oil and flour made from the ground seeds is used).

Cyperus this is the dried root of the aquatic plant, galingale Cyperus longus (see this page galingale on more information about the plant). Modern chefs would probably use Asian galengal instead.

Elecampane Inula helenium is a a perennial composite plant, also known as 'Horse-heal', a member of the Asteraceae (dais family) that is common in many parts of Great Britain, and ranges throughout central and Southern Europe, and in Asia as far eastwards as the Himalayas. The roots (which should be no more than three years old) are used both as a medicine and as a condiment.

Rue Ruta spp represents a family of strongly scented evergreen subshrubs native to the Mediterranean region, the most well known of which is common rue, Ruta graveolens. It is very bitter and the dried leaves should be used sparingly. As a potential abortifecant, it should never be consumed by pregnant women.

Wormwood Artemisia spp (but most commonly Artemisia absinthium [absinthe wormwood]), a herbaceous perennial plant, with a hard, woody rhizome, native to temperate regions of Eurasia and northern Africa. The leaves and flowering tops are gathered when the plant is in full bloom, and dried naturally or with artificial heat.

Mastic is a dried yellow resing dreived from from the mastic tree (Pistacia lentiscus). In antiquity it was used as a kind of chewing gum (hence the name) and even today it is used both as a flavouring and thickening agent, particularly in the Mediterranean region.

Hydrogarum this is the Roman name for a sauce or stock made by diluting garum (fish sauce, see above) with water.

Egyptian Bean Colocasia esculenta (Colocasio in Latin) was a plant much esteemed by the Romans (which we know of today as taro). As today, the starchy tubers were the most esteemed part and these were boiled, as we would prepare potatoes. However, the stems and leaves were also cooked and served, as were the plant's beans (substitute these with borad [fava] beans in any Roman recipe).

Feverfew Pyrethrum parthenium (Pyrethrum in Latin) is a is a traditional medicinal herb that is a member of the Asteraceae (daisy family) that has long been used for treating headaches, arthritis and digestive problems. Howeve, it can cause severe allergic reactions, mouth ulcers and should not be taken during pregnancy. This is a Roman ingredient to avoid.

Amulata (Amulum) — this is a starch made from wheat that's steeped in water and then macerated before being air dried. It is a classical Roman thickening agent, and a recipe is given by Cato in his De Agricultura (see Cato's recipe for amulum).

Caricarum This is a wine made from figs, made by macerating or boiling figs in water until they disintegrated. Typically this was boiled down until very thick and sweet.

Oxyporum This is a traditional Roman recipe for a salad dressing made from dates. You can find a modern version of the recipe here: Oxyporium Salad Dressing.

As well as information on Apicius and his recipes, I also include links to each chapter of the book (these have the original Latin text and an English translation) as well as providing links to modern versions of the recipes that you can cook at home. Below is also a glossary of various terms and ingredients that might be unfamiliar, as well as a list of substitutes. This site aims to provide the most complete collection of Roman recipes available on the web today.

Apicius' De Re Coquinaria — On Cooking

Frontispiece of the second edition of Martin Lister's

Frontispiece of the second edition of Martin Lister's privately printed version of Apicius 1709.

Introduction

The volume, De Re Coquinaria (On Cooking), sometimes known by the name of its purported author, Apicius is a collecton of Roman cookery recipes, usually thought to have been compiled in the late 4th or early 5th century Ce and written in a language that is in many ways closer to Vulgar than to Classical Latin.Apicius is a culinary text that's intended to be used in the kitchen. In the earliest printed editions, sometimes known under the title Ars magiricus, it was most usually given the overall title De re coquinaria ('On the Matter of Cooking'; or simply 'On Cooking'), and was attributed to an otherwise unknown 'Cœlius Apicius' (or 'Apicius Cœlius'), an invention based on the fact that one of the two extant manuscripts is headed with the words 'API CAE'.

The text itself is organised in ten books (or chapters) that, in essence, are arranged in a manner very similar to any modern cookbook. Namely:

I. Epimeles — The Careful Chef

II. Sarcoptes — Chopped Meats

III. Cepuros — From the Garden

IV. Pandecter — Various Dishes

V. Ospreos — Legumes

VI. Aeropetes — Fowl

VII. Polyteles — Gourmet Dishes

VIII. Tetrapus — Quadrupeds

IX. Thalassa — Seafood

X. Halieus — The Fisherman

The links above take you to diplomatic versions of the Latin text of Apicius (amassed from the various sources, critical editions and on-line versions available today), presented with a side-by-side translation into English and a link to a modern redaction of the recipe. My attempt has been to make Apicius both accessible and understandable by the modern cook. As a result this version of the text is less learned than many other sources. The same can be said of the English translation. It is an attempt to make Apicius understandable and useful to modern cooks, rather then giving a learned word-for word rendition into English.

II. Sarcoptes — Chopped Meats

III. Cepuros — From the Garden

IV. Pandecter — Various Dishes

V. Ospreos — Legumes

VI. Aeropetes — Fowl

VII. Polyteles — Gourmet Dishes

VIII. Tetrapus — Quadrupeds

IX. Thalassa — Seafood

X. Halieus — The Fisherman

The text however, is broken, indicative of many redactions. With some recipes in chapters not consistent with the chapter title. Some recipes are present in duplicate, some are believed to be truncated, sometimes a line seems to be missing.

In a completely different manuscript, there is also a very abbreviated epitome entitled Apici Excerpta a Vinidario, a 'pocket Apicius by Vinidarius, an illustrious man', that seems to have been penned as late as the Carolingian era. This text survives in a single 8th century uncial manuscript. However, despite the title, this booklet is not an excerpt from the earlier Apicius manuscript we have today (as a result it is reproduced in full on this site. It contains text that is not in the longer Apicius manuscripts; which suggests that either some text was lost between the time the excerpt was made and the time the manuscripts were written, or there never was a 'standard Apicius' text, because the contents changed over time as it was redacted and adapted by various readers of the text.

As a note, though Apicius is thought to have been compiled during the 4th and 5th centuries and it is possible that some recipes may date back to the time of the historical Apicius during the 1st century CE, the oldest extant manuscript we have is penned in the 10th century (c. 900 CA) in monastic-style uncial. This came from the monastery of Fulda in Germany, which was acquired in 1929 by the New York Academy of Medicine. An example page is given here, so you can see the text.

XI. Apici Excerpta — The Excerpts of Apicius

Who Was Apicius?

Even the name Apicius is shrouded in some mystery. However, the familial name Apicius seems to have been long-associated with excessively refined love of food, based on the exploits of two early Roman gourmands bearing the name. Imagined portrait of Marcus Gavius Apicius from

Imagined portrait of Marcus Gavius Apicius from Alexis Sawyer's Pantropheon, 1853.

About the time of Tiberius there lived a man named Apicius, very rich and luxurious; from whom several kinds of cheesecakes are called Apician. He spent countless sums on his belly, living chiefly at Minturnae, a city of Campania, eating very expensive crawfish, which are found in that place superior in size to those of Smyrna, or even to the crabs of Alexandria. Hearing too that they were very large in Africa, he sailed thither, without waiting a single day, and suffered exceedingly on his voyage. But when he came near the place, before he disembarked from the ship, (for his the news of his arrival had spread amongst the Africans,) the fishermen came alongside in their boats and brought him some very fine crawfish; and he, when he saw them, asked if they had any finer; and when they said that there were none finer than those which they brought, he, recollecting those at Minturnae, ordered the master of the ship to sail back the same way into Italy, without going near the land. But Aristoxenus, the philosopher of Cyrene, a real devotee of the philosophy of his country (from whom, hams cured in a particular way are called Aristoxeni), out of his prodigious luxury used to syringe the lettuces which grew in his garden with mead in the evening, and then, when he picked them in the morning, he would say that he, was eating green cheesecakes, which were sent up to him by the Earth.

When the emperor Trajanus was in Parthia, at a distance of many days’ journey from the sea, Apicius sent him fresh oysters, which he had kept so by a clever contrivance of his own; real oysters, — not like the sham anchovies which the cook of Nicomedes, king of the Bithynians, made in imitation of the real fish, and set before the king, when he expressed a wish for anchovies

When the emperor Trajanus was in Parthia, at a distance of many days’ journey from the sea, Apicius sent him fresh oysters, which he had kept so by a clever contrivance of his own; real oysters, — not like the sham anchovies which the cook of Nicomedes, king of the Bithynians, made in imitation of the real fish, and set before the king, when he expressed a wish for anchovies

Athenaeus also informs us that Apician recipes were famous and that many recipes were attributed to him. However, Apicius is not the only gourmand who has recipes attributed to them in the De Re Coquinaria. The most notable of these is Vitellius (who ruled Rome between January and June 69CE), a famous glutton. He ante-dates Apicius and it would seem that, rather than having been written by Apicius, the book was more likely dedicated to him. Indeed, 'Apicius' may even have become a short-hand for anyone who enjoyed their foods. So that a dedication to 'Apicius' in the general would be one to all gourmands.

Even then, the prototype for the generalized 'Apicius' is probably Marcus Gabius Apicius as he is the most famed of all bon-vivants. He established a school for the culinary arts, and according to such notable writers as Seneca and Martial, it is said that Apicius spent his vast fortune on food and when his reserves of gold had dwindled he took his own life, fearing that he might have to starve to death one day.

As the poet Martial writes in his Epigrams 3.22:

Dederas, Apicti, bis treceenties ventri,

et adjuc supererat centies tibi laxum.

hoc tu gravatus ut famem et sitim ferre

summa venenum potione perduxti.

nihil est, Apici, tibi gulosis factum.

In translation:

After you'd spent twice-thirty million on your belly, Apicius,

and there still remained a cool 10 million,

An embarrassment, you said, fit only to satisfy

Mere hunger and thirst:

So your last and most expensive meal was poison...

Apicius, you never were more a glutton than at the end.

et adjuc supererat centies tibi laxum.

hoc tu gravatus ut famem et sitim ferre

summa venenum potione perduxti.

nihil est, Apici, tibi gulosis factum.

In translation:

After you'd spent twice-thirty million on your belly, Apicius,

and there still remained a cool 10 million,

An embarrassment, you said, fit only to satisfy

Mere hunger and thirst:

So your last and most expensive meal was poison...

Apicius, you never were more a glutton than at the end.

In truth, even by the end of the first century CE, the very name of 'Apicius' had become a cliché for wealth and culinary excess. As Juvenal writes in his Satires (II. 2–3)

What greater joke tickles the ear of the people than the sight of a poor Apicius?

Whether Apicius was the author of the volume, or simply a figure or an archetype it was dedicated to, the De Re Coquinaria remains the first European cookery book, and an invaluable window on Roman food and Roman cookery. Many of the recipes are quite familiar in some ways, others are surprising in terms of their combination of flavours and even more are extremely modern in their use of fish sauce to provide the umami flavour to food (which we use anchovy essence, mushrooms and Worcestershire sauce for).

Origins of the Manuscripts

Image of De Re Coquinaria Fulda MSS c 900 CE.

Image of De Re Coquinaria Fulda MSS c 900 CE.

The Tours manuscript, (now in the Vatican Library [Urb. lat. 1146) is a highly decorated manuscript and was almost certainly not intended for everyday use in the kitchen. The Fulda manuscript seems to have come to Italy in 1455 and was acquired by the Philips collection, Cheltenham in the early nineteenth century. It now resides in the library of the Academy of Medicine, New York.

Both manuscripts derive from a common antecedent which seems to have been located at Fulda. This was extant in the fifteenth century, when Poggio made his excerpts.

In the fifth or sixth century, an Ostrogoth, Vinidarius, who lived in Northern Italy made some excerpts of Apicius and these now survive in a single eighth century unical manuscript, the codex of Salmasius, sæc. VIII, Paris, lat. 10318.

The language of both the extant early manuscripts is popular (Vulgate) Latin and not the classical Latin of Apicius' time (assuming he existed). Indeed, if there was an original classical Latin antecedent this was copied and re-worked by an editor who lived in the late fourth or early fifth centuries.

Indeed, this unknown editor may be the true creator of the Apicius manuscript, as there is evidence that the brought together recipes from several sources (one of which was the cookery of Apicius, the other being the writings of Apuleius).

As such, there may never have been a 'starndard Apicius', as each generation updated, extended and amended the text to suit their own culinary purposes. Indeed, Vinidarius' excerpts suggests at the existence of at least one other version of Apicius with recipes that do not exist in the extant manuscripts. As a result, Vinidarius' excerpts are, today, invariably included as an eleventh chapter to supplement the ten of the standard Apician cookbook that has come down to us.

Printed Manuscripts

The first printed editions of the manuscript date to the fifteenth century. These now exist in various libraries, but all originate from Northern Europe during the renaissance and were based on the Vatican codex. The oldest of these was printed in 1498, based on a privilege that the Duke of Milan granted to Ioannes Passiranus de Asula in 1497 for a five-year copyright to reproduce six Latin texts, one of which was Apicius de ciibaris. This is now acknowledged as the editio princeps of all the printed versions of Apicius.This edition seems to have been re-printed in Venice c. 1500, but it was printed anonymously and without a date (probably to try and avoid any difficulties regarding the Milanese privilege), which was then used as the model for the edition of Ioannes Tacuinus (Venice, 1503).

In 1541, Albanus Torinus produced the first critical edition of the text (Basle, 1541) that gave a partial translation into humanist Latin. The following year, Gabriel Humelberg published a new edition (Zürich, 1542), basing his texts on good manuscripts, as well as well as what he calls an antiquum manuscritum exemplar now, unfortunately, lost to us.

This was the edition that Martin Lister (physician to Queen Anne) followed closely for his own edition (London, 1705; Amsterdam 1709). The first translation was into Italian in 1852, followed in the 20th century by two translations into German and French.

The first truly reliable edition of the Latin text was that of C Giarratano and F Vollmer (Leipzig, Teubner, 1922). Vehling made the first translation of the book into English under the title Cookery and Dining in Imperial Rome. It was published in 1936. The translation is still in print, having been reprinted in 1977 by Dover Publications. Today, however, this version is of little more than historical interest only and several more recent translations exist, including the one presented on this site.

Roman Cookery

For more information on Roman ingredients, herbs and spices, fruit and vegetables, the principles of Roman cookery and the Roman kitchen, please use the links below:The Flavours of Roman Cookery

Roman Herbs and Spices

A Guide to Roman Ingredients

The Roman Kitchen

Terms in Apicius

There are many ingredients in Apicus that won't be familiar to the modern cook. As a result I present a glossary of these terms below, as well as substitutes for many of the rarer ingredients that will not affect the overall flavour of any dish.Glossary to Terms in Apicius

Laser: Also referred to as silphium, is generally considered to be a form of 'giant fennel' (Ferula tingaitana), with the spice being the dried resin of the plant, that became extinct in North Africa due to over-harvesting (and was imported instead from Syria, Iraq and Iran) and formed the crux of trade from Cyrene (modern Lybia) to the Roman empire. The valuable product was the resin (laser, laserpicium, or lasarpicium) of the plant. It was harvested in a manner similar to asafoetida (Indian hing), a plant with similar enough qualities to silphium that Romans, including the geographer Strabo, used the same word to describe both. The plant became extinct during the first century CE, probably due to a combination of over-collection and over-grazing (but has returned there in modern times). The Romans substituted asafoetida, though the taste was deemed 'not as good'. Modern cooks tend to use fennel or ginger for the same effect. But asafoetida (known as 'hing' in Indian cookery) is a common enough spice that it can be used in any Roman recipe calling for 'laser' or 'silphium'.Defritum: Referred to in some translations as 'boiled wine', defritum is wine boiled down to half its original volume before use.

Caroenum This is boiled Must (must is essentially very young wine [at the first stage of fermentation]). The closest modern equivalent would be a sweet young white wine or grape juice. Boil until the volume is reduced by half.

Sapa: This is must (grape juice) that is boiled down to a third of its original volume. It was made with sweet wine and the final product was both very thick and sweet. It was used as a sweetener and flavouring as well as a preservative (in place of honey).

Liquamen: Traditionally this is thought of as a 'cheap form' of fish sauce (see garum below). But, reading Apicius carefully reveals that liquamen is used as a generic term for a sauce or stock of any kind. In many cases this would have been a fish sauce, but could have been any kind of meat, fowl, vegetable, shellfish, fish or seafood sauce. Indeed, the inference seems to be that the cook should know what kind of stock or sauce was appropriate to the sish.

Garum: Fermented salted fish. This was a common addition to Roman food. The closest modern equivalent would be Nam Pla, Thai fish sauce. However, if you are interested in making your own Roman fish sauce, I do have a recipe: how to make Garum. Note that, in some circumstances, Liquamen (see above) can also refer to fish sauce.

Passum This is a sweet wine sauce made by adding honey to must (or raisin wine) and boiling until it has thickened.

Puledimu This is Pennyroyal (Mentha pulegium). Ordinary garden mint can be substituted.

Sautreia This is Summer savory Satureia hortensia. The commoner winter savory can be substituted for this.

Silphium See laser, above.

Spikenard This is the plant, Nardostachys grandiflora (Indian spikenard) or Nardostachys jatamansi (Himalayan spikenard), [also known as nard, nardin, and muskroot] an aromatic plant with small leaves and red-purple flowers that's a member of the Valerian family and a native to northern region of India and Nepal as well as the Himalayas of China. This is used frequently in aromatherapy oils. The oil was known in ancient times and was obtained as a luxury in ancient Egypt, the Near East, and Rome, where it was the main ingredient of the perfume nardinum. The dried root, used as a spice, be obtained from a specialized supplier. An alternate is to use equal portions of fennel and lavender a fifth of the final quantity of valerian root (note, valerian is a sedative and some people are very sensitive, use sparingly. Lavender should not be consumed by pregnant women). The powdered root was used commonly as a spice during Roman times and in Medieval Europe it was part of the spice blend used to flavour Hypocras. For more information about spikenard, and spikenard recipes see the Spice Guide entry for Spikenard.

Safflower This is the plant, Carthamus tinctorius, a highly branched, herbaceous, thistle-like annual that is growh both for its seeds (used to make oil) and for the dried petals that can be used as a saffron substitute. In ancient times, it was prized by the Egyptians and the use in Apicius clearly demonstrates the Egyptian antecedents of some of the recipes (where the oil and flour made from the ground seeds is used).

Cyperus this is the dried root of the aquatic plant, galingale Cyperus longus (see this page galingale on more information about the plant). Modern chefs would probably use Asian galengal instead.

Elecampane Inula helenium is a a perennial composite plant, also known as 'Horse-heal', a member of the Asteraceae (dais family) that is common in many parts of Great Britain, and ranges throughout central and Southern Europe, and in Asia as far eastwards as the Himalayas. The roots (which should be no more than three years old) are used both as a medicine and as a condiment.

Rue Ruta spp represents a family of strongly scented evergreen subshrubs native to the Mediterranean region, the most well known of which is common rue, Ruta graveolens. It is very bitter and the dried leaves should be used sparingly. As a potential abortifecant, it should never be consumed by pregnant women.

Wormwood Artemisia spp (but most commonly Artemisia absinthium [absinthe wormwood]), a herbaceous perennial plant, with a hard, woody rhizome, native to temperate regions of Eurasia and northern Africa. The leaves and flowering tops are gathered when the plant is in full bloom, and dried naturally or with artificial heat.

Mastic is a dried yellow resing dreived from from the mastic tree (Pistacia lentiscus). In antiquity it was used as a kind of chewing gum (hence the name) and even today it is used both as a flavouring and thickening agent, particularly in the Mediterranean region.

Hydrogarum this is the Roman name for a sauce or stock made by diluting garum (fish sauce, see above) with water.

Egyptian Bean Colocasia esculenta (Colocasio in Latin) was a plant much esteemed by the Romans (which we know of today as taro). As today, the starchy tubers were the most esteemed part and these were boiled, as we would prepare potatoes. However, the stems and leaves were also cooked and served, as were the plant's beans (substitute these with borad [fava] beans in any Roman recipe).

Feverfew Pyrethrum parthenium (Pyrethrum in Latin) is a is a traditional medicinal herb that is a member of the Asteraceae (daisy family) that has long been used for treating headaches, arthritis and digestive problems. Howeve, it can cause severe allergic reactions, mouth ulcers and should not be taken during pregnancy. This is a Roman ingredient to avoid.

Amulata (Amulum) — this is a starch made from wheat that's steeped in water and then macerated before being air dried. It is a classical Roman thickening agent, and a recipe is given by Cato in his De Agricultura (see Cato's recipe for amulum).

Caricarum This is a wine made from figs, made by macerating or boiling figs in water until they disintegrated. Typically this was boiled down until very thick and sweet.

Oxyporum This is a traditional Roman recipe for a salad dressing made from dates. You can find a modern version of the recipe here: Oxyporium Salad Dressing.

Recipe Substitutions

The following are Apician ingredients that can be safely substituted with modern alternatives, without markedly changing the nature of the dish.| alecost | — | mint (Emperor's mint would be best) | chervil | — | aniseed and parsley (combined) | colewort | — | mustard seeds | costmary | — | mint (Emperor's mint would be best) | cyperus (root) | — | galangal (or ginger) | Damascus plums | — | damsons | Egypican bean root | — | taro, eddoes or cocoyam | Egyptian beans | — | broad (fava) beans | elcampane | — | mint | pennywort | — | peppermint |

Roman Weights and Measures

| Roman Measures | Imperial Equivalent | Metric Equivalent |

| libra [Roman pound] | 0.75 pound | 327g |

| semilibra [half Roman pound] | 0.375 pound | 163.5g |

| unica [Roman ounce] | 0.96 ounce | 27g |

| scripulum [Roman scruple] | 1/24 ounce | 1.136g |

| six scruples | 1 tsp | 5ml |

| sextarius [Roman pint] | 0.96 pints | 540ml |

| hemina [Roman half pint] | 0.48 pints | 270ml |

| quartarius [Roman quarter pint] | 0.24 pints | 135ml |

| acetabulum [1/8 Roman pint] | 0.12 pints | 67.5ml |

| cyanthus [1/12 Roman pint] | 0.08 pints | 45ml |

| coclearum [literally: "snail's shell"] | 1 tsp | 5ml |

| coclearum dimidium [half a snail's shell] | 1/2 tsp | 2.5ml |