FabulousFusionFood's Alexis Soyer Recipes from the Victorian Age Home Page

Drawing of Alexis Bénoist Soyer 1810–1858.

Drawing of Alexis Bénoist Soyer 1810–1858.

Welcome to FabulousFusionFood's Alexis Bénoist Soyer Recipes Page — This page brings together all the recipes on this site redacted (updated) from various of Alexis Soyer's Victorian recipe books. All recipes are given both in their original form and as a modern redaction that and cook today could follow so that you, too, can prepare classic Victorian fare at home. Below I also provide a brief outline on Alexis Soyer's life and more information about his various books. I am making my way through the entire recipe collection and as soon as they are added to my site they will be available here. (For the recipe list scroll down.) Enjoy...

Alexis Bénoist Soyer

February 4th 1810–August 5th 1858

Alexis Bénoist Soyer was born on the 4th of February 1810 at the Rue Cornillon, Meaux-en-Brie, France. He was the youngest son of Emery Roch Alexis Soyer and Marie MAdeleine Françoise Chamberlain, formerly grocers grocers of Rue du Tan, Meaux-en-Brie. By Alexis' birth the family had fallen on hard times and they were no longer grocers. To support the family, his father had to take on several jobs (one of which was working on the local canal as a labourer).

Alexis was the youngest of five brothers, though only he and his elder brothers Philippe and Louis survived beyond childhood. It is said that Alexis' mother wanted him to join the church. However, Alexis had other ideas and by the age of 11 (in 1821) he was expelled from school and left to join his brother Philippe in Paris, becoming apprenticed to the chef George Rignon at the Grignon restaurant . By this time Philippe was already an established chef. In 1826 Alexis moved to the Boulevard des Italiens restaurant, where he became a chief cook and by the age of 17 Alexis himself was a celebrated chef with a dozen junior chefs working for him. By 1830 Soyer had become the second cook to Prince Polignac, the French prime minister.

In 1830 revolution came to France and during the Les Trois Glorieuses Soyer fled to England. He joined the London household of Prince Adolphus Guelph, Duke of Cambridge (his brother was already head chef there). During the next six years, Alexis quickly established himself with the gentry as a chef of note and he worked for various other British notables, including the Duke of Sutherland, the Marquess of Waterford, William Lloyd of Aston Hall and the Marquess of Ailsa at St Margaret’s House, beside the Thames and Priory Gardens in Whitehall.

In 1837, he married the celebrated artist, Elizabeth Emma Jones. Emma (as she preferred to be called) achieved considerable popularity as a painter, chiefly of portraits. She was one of the youngest persons to exhibit at the Royal Academy; in 1823, at the age of 10, she submitted the Watercress Woman. Her portrait of Soyer was engraved by Henry Bryan Hall. She died in 1842 following complications suffered in a premature childbirth brought on by a thunderstorm. Distraught, Soyer erected a monument to her at Kensal Green Cemetery.

The other great love in Alexis Soyer's life was Fanny Cerito, one of the leading ballerinas of the day. Fanny's father disapproved of the relationship and she married Arthur St Leon instead, but the marriage failed. She and Alexis maintained a secret relationship until his death.

In 1837, Alexis Soyer was offered the position of chef de cuisine at the Reform Club in London. He personally designed the kitchens with Charles Barry (the club was newly built) and began his job with a salary of over £1000 per annum. During his time at the club he instituted many innovations, including cooking with gas, refrigerators cooled by cold water, and ovens with adjustable temperatures — indeed, his kitchens at the club were so famous that they were opened for conducted tours.

For Queen Victoria's coronation on the 28th June 1838, he prepared a breakfast for 2,000 people at the Club. His famous Lamb Cutlets Reform is still served at the club.

During the height of the Great Irish Famine (1845–1849) of 1847, Alexis Soyer was asked by Russell's government (April of that year) for help. The Reform Club gave him a leave of absence and Soyer went to Dublin, where he established the first properly-designed soup kitchen. There he served the Famine Soup which he had formulated himself. At the peak of the famine he served the soup, free, to up to five thousand people per day. During this time Alexis' offerings were pivotal in saving hundreds of lives. While in Ireland he wrote Soyer's Charitable Cookery. He gave the proceeds of the book to various charities. He also opened an art gallery in London, called 'Soyer's Philanthropic Gallery' which showed pictures painted by his late wife. He used all the proceeds from this venture to establish several soup kitchens in various districts of London to feed the poor.

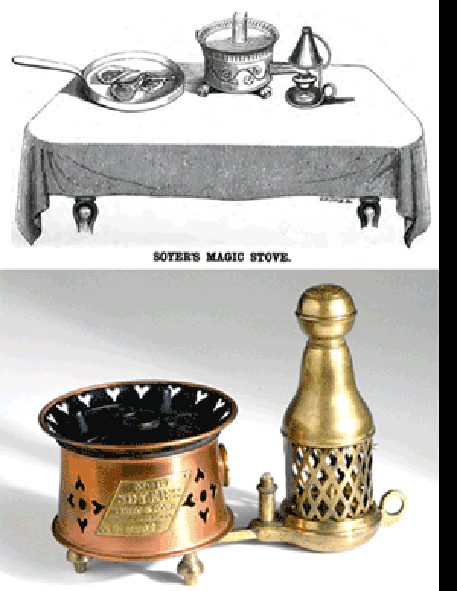

Alexis Soyer magic stove, original engraving and picture of the apparatus

Alexis Soyer magic stove, original engraving and picture of the apparatus

Alexis Soyer had threatened to resign from the Reform club several times during his tenure there (most notably in 1848). He tendered his resignation again in 1859, using as a pretext that the club were to allow members into the coffee room. Alexis had always been concerned about 'consumption' (tuberculosis), having lost several family members to the disease, including both his brothers (Philippe died of the disease in 1840). This was then used as the sub-text for his resignation. This time, the club's president, Lord Marcus Hill accepted the resignation (though Marcus Hill himself remained a lifelong-friend to Alexis).

In the latter part of 1850, Alexis entered into partnership with Joseph Feeney (later George Symonds) to lease Gore House (which stood where the Royal Albert Hall now stands) and which was then opposite the gates of the 1851 Great Exhibition. At Gore House, he established 'Soyer's Universal Symposium', the most flamboyant and fashionable restaurant ever seen in London. Each 'salle' (room) was decked in an extravagant theme (eg: Le Grotte Des Neiges Eternelles and La Chambre Ardante D'Apollo). He hoped to entertain 5000 people per day in the restaurant, with different-priced menus. However, prices spiralled and after only three months he was forced to close it down at a loss of £7000.

The years 1851 to 1855 were spent in touring the country, where Alexis Soyer promoted his cookbooks and his 'magic stove'. He also oversaw and masterminded sumptuous banquets and feasts, always with the proviso that any left-overs be given to the poor.

In 1855 Soyer became concerned about the plights of the troops fighting in the Crimea. The papers, most notably the Times contained frequent reports of the atrocious conditions in the hospitals at Scutari and Balaclava, the poor rations of the soldiers and the deaths from food poisoning, malnutrition and cholera. He volunteered, at his town expense, to join the troops to advise the army on cooking. Through the auspices of the Duchess of Sutherland he obtained Lord Panmure's authority to correct any matters he saw fit. He reorganized the provisioning of the army hospitals. He designed his own field stove, the Soyer Stove, and trained and installed in every regiment the "Regimental cook" so that soldiers would get an adequate meal and not suffer from malnutrition or die of food poisoning. His efforts led to him being eventually paid his expenses and wages equivalent to those of a Brigadier-General. The Soyer's Field Stove was still being used by the British Army 120 years later.

Soyer also worked in close liaison with Florence Nightingale to improve the dietary and food regimens of the field hospitals. As a result, the Morning Chronicle said of Soyer that he saved as many lives through his kitchens as Florence Nightingale did through her wards. Alexis Soyer wrote his A Culinary Campaign as a record of his activities in the Crimea.

Soyer returned to London on the 3rd May 1857. On 18 March 1858, he lectured at the United Service Institution on army cooking. He also built a model kitchen at the Wellington Barracks in London. However, his time in the Crimea had affected him and by the time he returned to London he was not a well man. He died on August 5th 1858 and is buried with his wife, under the memorial 'Faith' in Kensal Green Cemetary, London.

Alexis Soyer's Inventions

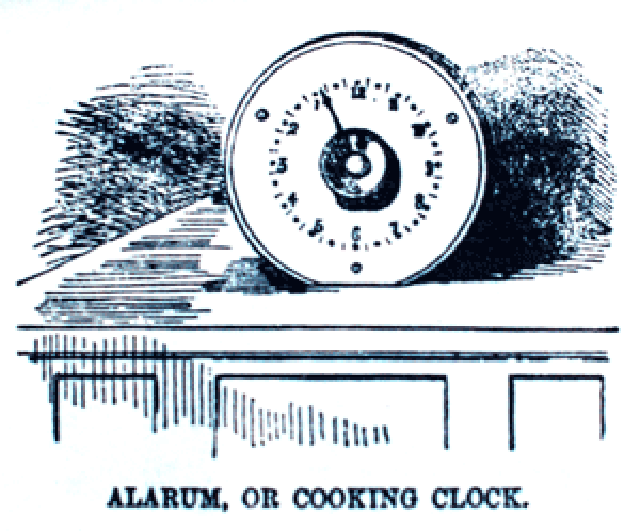

Alexis Soyer Kitchen Timer

Alexis Soyer Kitchen TimerBut there is one Soyer invention that is in almost every kitchen today. Because it was he who invented the cook's timer (see the image here), a small clock where an alarm would sound after a certain cooking time.

Alexis Soyer's Books

It is said that Soyer never lifted a pen to write, except to sign his name. However, during his writing career, he always employed two secretaries, one fluent in French and the other fluent in English who would take dictation for him. His wife, also, acted as a secretary whilst she was alive.His list of works follows:

Délassements Culinaires. (1845)

The Gastronomic Regenerator (1846)

Soyer's Charitable Cookery (1847)

The Poorman's Regenerator (1848)

The modern Housewife or ménagère (1849)

The Pantropheon or A history of food and its preparation in ancient times (1853).

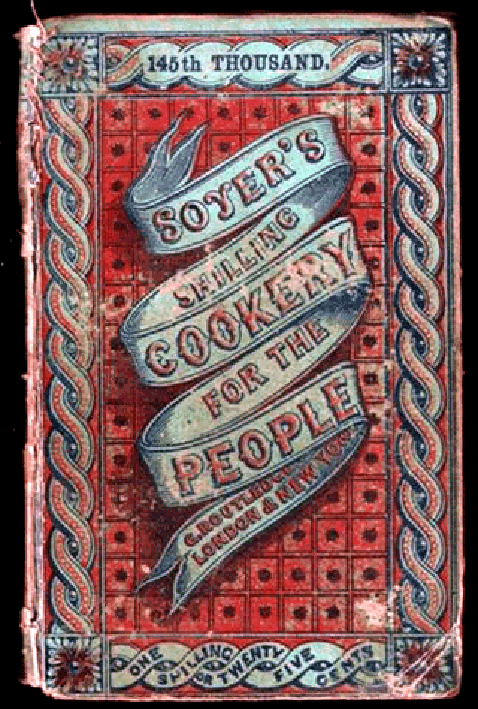

A Shilling Cookery Book for the People (1854)

Soyer's Culinary Campaign (1857)

Instructions for Military Hospital Cooks (1860) [published posthumously]

Of these, it appears now that Soyer did not write the Pantropheon, though Soyer retained attribution for himself. Rather, it was wirtten by M. Adolphe Duhart-Fauvet and only the final chapter Modern Banquet was written by Soyer himself.

Soyer's Reputation

As an ardent self-publicist, Soyer controlled much of his own reputation and fame. In this he has some claim to be the First Celebrity Chef. His fame was widespread and during his own lifetime he was considered 'The Greatest Chef in the World'.Of course, he was a product of his time and was a true Victorian entrepreneur. The only way to become known was to be written about in the papers and to travel the country. He was a renaissance man, as a culinary artist, a writer and an inventor. But, like man Victorians he also had a social conscience.

His good works cannot be ignored, from the Irish Potato Famine to improving the lot of the common soldier. By inventing Soup Kitchens and new cooking techniques he has saved thousands of lives. He was also actively involved in improving the conditions and nutrition of the poor. This is a recurring theme throughout his life and career, and what prompted him to write his A Shilling Cookery Book for the People, a series of recipes that could be cooked with a minimal set of common utensils. This was intended to improve the lot of the poor. The irony being, that the price of the book and illiteracy amongst the poorer classes meant that they either could not read or could not afford to read the book.

Alexis Soyer Shilling Cookery for the People, original cover image

Alexis Soyer Shilling Cookery for the People, original cover imageThe other irony of Soyer's life is that, for a man who lived his life in the public gaze, he became almost forgotten by history. The truth is that upon his death, all his assets were seized by a creditor, David Hart, a wine merchant. All Soyers' paperwork and the notes of his life were lost. As a result, the details of his life were effectively erased from history and a man who achieved so much became forgotten.

And where cookery writers such as Hannah Glasse and Eliza Acton have their champions Alexis Bénoit Soyer has vanished into obscurity. He is probably less well known today than even his contemporary, Charles Elmé Francatelli. That a man who did so much to improve British life in his adopted homeland should be so completely ignored is a real disgrace.

It's this site's aim to provide the original text of all the Soyer recipes and to provide the modern cook with a current redaction of the recipe. You can also find more recipes from the Victorian period in this site's Victorian recipes page.

The alphabetical list of all the Alexis Bénoist Soyer recipes on this site follows, (limited to 100 recipes per page). There are 4 recipes in total:

Page 1 of 1

| Melted Butter Origin: Britain | Skate Curry Origin: Britain |

| Nettles Origin: British | Spotted Dick Origin: Britain |

Page 1 of 1